High-Tech and Low: Digitally Drawn versus Traditional Illustration

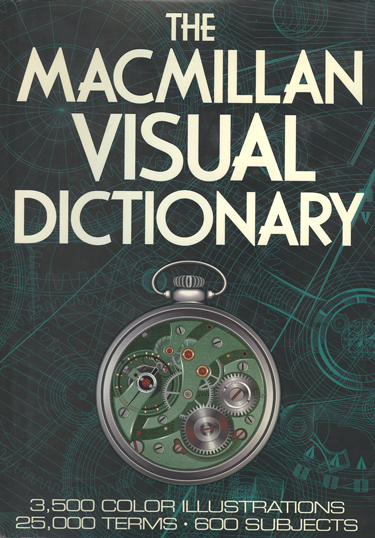

In the early 90s, as an art director at Macmillan Publishing, one of the book projects on my list was the 1st edition of The Macmillan Visual Dictionary. What made this book stand out at the time were the visually consistent digitally drawn illustrations.

When I first got to see the artwork being created on the computer, I remember being amazed. Quebec / Amerique International would send us interior proofs to look over. It was also a massive undertaking because it was such a huge book, with 3,500 color illustrations being created for the interior.

Selecting the art that would be on the cover was easy for me because I felt the timelessness of their “inner-workings of a pocket watch” would work very well. It was an image that would be easily recognized and could help illustrate what would be discovered inside.

Later on, Macmillan created the Multilingual version (English, Spanish, French and German) and other books in the series. One of the complimentary books was “The Macmillan Dictionary of Measurement.” This book interior was going to be mostly text, but it did have 50 black and white drawings, so I needed to find the right illustrator for the cover that would compliment the series.

Peter Thorpe was the perfect illustrator for that cover project because his style is realism but (as he says) with a design attitude. The “sextant” was painted with thinly used acrylic (like watercolor) on 100% cotton illustration board. Peter made sure the technical vignette illustration had clean edges so the background could be knocked out.

I asked Peter about that artwork and how he has embraced the computer since those days, for both his illustration and graphic design.

“Well I did embrace it. First, I said a happy good-bye to ordering type, getting a black and white print out, waxing (!) the back and burnishing it down on a board with crop marks, and a tissue overlay with instructions. Suddenly, I could do type, mechanical, background colors, etc… on the computer.

Absolute heaven.

I didn’t really scan art much at first, because my computer mechanical and the original art then went to the publisher. They did the rest and returned the art to me. But eventually I did just scan my own art and added to the mechanical, and that opened new possibilities, like cropping, fades, bumping color, etc.”

– Peter Thorpe, Illustrator and designer

Back in the early 90s, so many artists were just beginning to use computers for graphic design, and many artists continued to draw and paint on paper or board, the same as always.

I did a search on Google for the “1st digitally illustrated book” and here’s what I found…

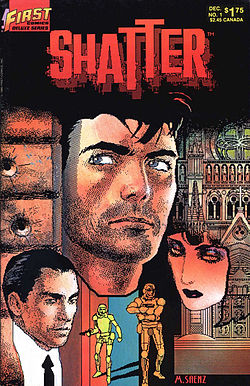

Shatter

The first episode of Shatter appeared in the March 1985 issue (#12) of computer magazine Big K (IPC Media, London with Tony Tyler as editor) and was described as “the world’s first comics series entirely drawn on a computer.”

The first episode of Shatter appeared in the March 1985 issue (#12) of computer magazine Big K (IPC Media, London with Tony Tyler as editor) and was described as “the world’s first comics series entirely drawn on a computer.”

Shatter is a digital comic created by Peter B. Gillis and Mike Saenz, and published by First Comics. A dystopian science fiction fantasy somewhat in the mold of Blade Runner, Shatter was written by Gillis and illustrated on the computer by Saenz.

Shatter was the first commercially published all-digital comic, i.e. a comic for which the art was created entirely on the computer; as opposed to what later became the common method of drawing on board with pencil, pen, and ink and then scanning the black-and-white art into a computer for the application of color.

The Shatter artwork was initially drawn on a first-generation Apple Macintosh using a mouse, and printed out on an Apple dot-matrix ImageWriter. The print-outs were then photographed like a piece of traditionally drawn black-and-white comic art, and the color separations were applied in the traditional manner for comics at the time. (This is almost the reverse of the current method of drawing comics on board and scanning the art into a computer for the application of color in computer graphics programs.)

Today, I find that it’s still a combination of techniques and what works best for each artist depending on their style. Some artists draw sketches in blank books to experiment with styling, technique, color, look, and typography. Some photograph or scan the drawings and finished paintings into the computer and then can enhance the art if needed. Some draw directly onto the computer using a Wacom tablet and stylus.

I would say that the computer has given us additional tools for our creative toolbox, but as others may agree, the conceptualization hits the brain first, then we decide how and what to use to implement the ideas.

6 thoughts on “High-Tech and Low: Digitally Drawn versus Traditional Illustration”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Shatter may be the first computer generated comic, but The Iron Man graphic novel “Crash” is probably the first computer generated graphic novel (or so it said on its cover). It came out in the late 80s-early 90s, and at the time may have been tremendous advance, but, of course, now it might come across as an antique.

How cool Mark! Here’s a link to the Iron Man graphic novel “Crash” so readers can check it out. It says it was published April 1988: http://marvel.wikia.com/Iron_Man_Graphic_Novel:_Crash_Vol_1_1

In the last millennium, when we occasionally had interns in our studio, it used to freak us out when we assigned them a task and they went straight to the computer. No, no no, we said. Sit down with paper and pencil first and think, then sketch, then think some more. And when you can’t think anymore, take your sketch over to the computer and make some magic. So we echo your sound opinion that graphic designers should get the concept going first before selecting the tools to make it happen.

Thanks, Jay! No to the potchka on the computer. With pencil and paper so you are pushing forth your ideas.

I feel lucky—and kind of old—to have spanned the generations in terms of traditional vs digital illustration. Good fundamentals translate to well-crafted illustration—that much has not changed in all these years. The same applies to creating letterforms digitally. Interesting in that we are now a solid generation into the digital age, and with that we have a generation of art buys and creative directors who have known nothing BUT digital.

As for me, I work in Illustrator 95% of my day, every working day, for something like 23 years now, and it’s all good. The fanciest pencil, rapidograph pen, or airbrush in the world. Another tool, and a very versatile one at that.

Thanks, Todd. Yes, I know just what you mean. I think back to those earlier times working at our drafting tables. How far we have come and who knows what’s ahead!

– Sue